China, a demographic giant with feet of clay

China, the world’s largest country in terms of population, is now a predominant player on the international economic and geopolitical stage.

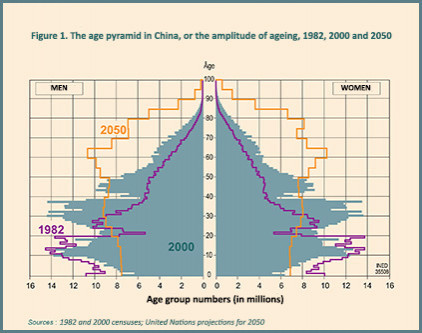

China owes its frontline position first and foremost to its population: 1.3 billion inhabitants today, a fifth of humanity, ahead of India and Africa. Yet according to the latest demographic projections of the United Nations (2012), the Chinese population might never reach 1.5 billion inhabitants, peaking instead at 1.45 billion in 2030, then starting to decline.

The "demographic bonus" will not last

China enjoys a considerable advantage today over its main rivals on

the world economic stage: 70% of its population is of working age

(15-59), as against 65% in Brazil, 62% in India, 60% in Western

Europe and North America, and 54% in Japan. The proportion of

economically dependent persons (children and old people) is

therefore extremely low. But this "demographic bonus" is a stimulus

to economic growth, but it will not last. As early as 2050, China

will have 220 million fewer persons of working age than at present.

A workforce deficit already looms in certain sectors.

Falls in fertility and increased life expectancy are constantly

upsetting the age structure of the Chinese population. And the

authorities are becoming concerned about demographic ageing, which

looks set to occur very quickly. According to United Nations

demographic projections, the proportion of people aged 65 or over,

7% in 2000, should more than triple by 2050, reaching 24%. China

will then have 330 million older people.

...and the scarcity of women persists

Another characteristic that is likely to weaken Chinese society is the lack of women. China is one of the few countries in the world with a majority of men: 104.9 for 100 women in 2010. This ratio positions it just behind India, the most "male" country in the world, with 106.4 men for 100 women in 2011 (as against 98.5 in the rest of the world).

As in India, China’s excessively male population is due to two factors: the increasing practice of selective abortion, which targets girls, and an abnormally high female mortality rate due untreated health problems in infants and young girls.

Chinese society’s preference for sons is the result of its patriarchal system and Confucianism, which keeps women in a secondary position within the family and society. Sons have the privilege of perpetuating the family line and the duty to take care of their parents in old age. Moreover, because couples have to place strict limits on the number of children they can have, daughters become undesirable simply because they deprive parents of the possibility of having a son.

But coercion due to China’s family planning policy is not the only explanation. Changes in reproductive behavior also play a role: having a small family has become the Chinese way. In the context of the country’s economic reforms, rising costs of living and social liberalization, more and more couples are spontaneously limiting family size. The desire to reduce number of descendants, combined with the firmly rooted preference for boys, explains the considerable rise in sex-selective abortion.

In addition, health system liberalization is considerably

increasing the cost of access to treatment, forcing families to

calculate the costs and benefits of obtaining medical care for

their children. The repercussions of this vary by sex: being less

valued, girls also show a higher infant mortality rate than

boys.

Raising a son for one’s old age

Despite the economic modernization of the last decades, gender

roles remain deep-rooted in China and Chinese women are not valued

as Chinese men are. In the patriarchal clan system that constituted

the foundation of this society, people were expected to get married

at a young age and have many children-especially sons. Today’s

society is no longer organized around the clan, but clan ideology

continues to have a presence in daily life.

While a family’s wealth is no longer transmitted solely to its

sons, patrilocal marriage remains the rule. When a girl marries,

she is still expected to leave her biological family and devote

herself to her husband’s family; she is not called upon to take

care of her own parents in their old age, as this responsibility

falls to sons and daughters-in-law. In the countryside, where there

is no extensive, efficient retirement system, it is still important

to "raise a son in anticipation of one’s old age." For hundreds of

millions of peasants, a son is the only pension scheme, and quite

often the only guarantee against disease or disability.

Imbalances on the marriage market

The demographic repercussions of the deficit in girls are

considerable. While for the last thirty years the deficit has

primarily concerned the child population, it is beginning to impact

on the adult population as the girl-scarce cohorts grow up. The

surplus of men is estimated at 10% to 15% of successive age

cohorts, a situation that has begun falling into place in the

2010s.

Male marriage candidates will now have to accept greater age gaps between spouses and longer wife-prospecting time, meaning their own marriage age should rise. To respond in part to the reduced availability of female partners, national and transnational networks are being set up. Rising numbers of women are crossing the border between Vietnam and China in search of husbands, for example. There are two reasons for this: the particularly acute scarcity of women in China’s southern provinces, and the rise in marriage costs for men since the economic reforms of the 1980s. Women-trafficking networks have been regularly dismantled in the last few years. For poor, relatively uneducated peasants, it is cheaper to turn to traffickers than to seek a wife through the traditional channels. Furthermore, the demand for wives on the part of Chinese peasants dovetails with Vietnamese women migrants’ own economic strategies, their hope that this type of marriage will provide them with a better life.

A central preoccupation of the Chinese

authorities

Various laws in China dating from the 1990s prohibit ill treatment

or discrimination against girls, notably infanticide or abortion,

along with prenatal sex discernment and the practice of selective

abortion. The "Care for girls" campaign launched in 2001 seeks to

promote the idea of equality between the sexes, namely in school

textbooks, and to improve the living conditions of families without

sons. In certain regions, for example, the couples in question

benefit from a support fund and are exempt from paying farm taxes

and compulsory school tuition for girls up to marrying age. The

effects of this campaign cannot yet be measured, however. The most

recent census (2010) revealed a male-female birth ratio that is

still much higher than the norm: around 120 boys are born for 100

girls, as against 105 to 106 in ordinary circumstances.

Isabelle Attané

Email: attane@ined.fr

Links for more info

-

China, the world’s most masculine country [focus on]

-

Watering the neighbour’s garden [publication]

-

Une Chine sans femme [publication]

-

Population and Societies n° 416

-

Population and Sociétés, n° 404

-

Figures : All the countries in the world

-

World Population in Graphs [animation]

-

Imagine the Population of tomorrow [animation]