Fertility and public policy: a comparison of France and Italy in tribute to Valeria Solesin’s thesis work

Valeria Solesin, one of the persons killed in the 13 November 2015 attacks in Paris, was trained as a sociologist and demographer. At the time of her death she was in the last phase of completing her doctoral thesis on contemporary fertility behaviours in Italy and France, with a special focus on the transition from first to second child. The aims of her thesis were well served by a rich combination of quantitative and qualitative methods (statistics and demographics, interviews). And she had already completed a substantial field study, in which she questioned around 60 parents with one or two children in France and Italy to better understand the motivations driving actors’ family-building choices and the mechanisms underlying them.

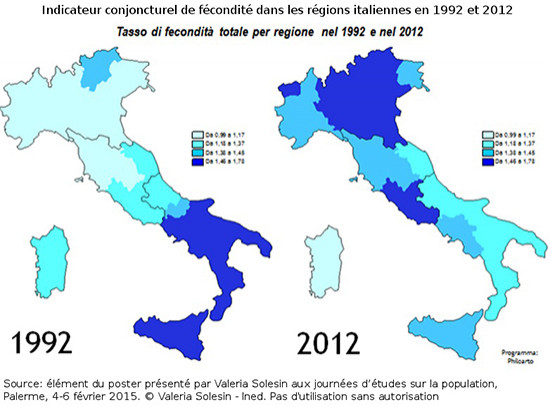

In 2014, the fertility indicator in Italy stood at 1.37 children per woman, as against 2.01 in France. The fall in Italian fertility is explained by a variety of factors. And different demographic features help account for the country’s particularly low fertility rate: the proportion of women who have not had children by the end of their childbearing years; postponement of first child, associated with late departure from the parental home; and the specific role of marriage. For many Italians, the only acceptable reason to leave the parental home is to get married, and doing so depends on obtaining independent housing, in turn related to the partners’ material situation in hard economic times. Given the weight of social norms in the country, couples seldom have children out of wedlock, in contrast to the situation in France.

Women’s labour market participation greatly increased in Europe in recent decades, but there are still considerable differences between countries. In fact, fertility is higher today in countries where women’s employment rate is high. The possibilities women are offered for combining work and family life in a relatively comfortable way seem a decisive factor for fertility in Europe. According to OECD data for 2010, 83% of women aged 24 to 54 in France are in work as against only 63% in Italy.

Italian women’s low participation in the labour market is due to general differences in norms and perceptions—what Ronald Rindfuss sums up with the notion of “family package.” That “package” may contain several constraints, particularly for women, who in many societies undergo heavy pressure to fit into well-defined roles; i.e., to be married, accept patriarchal norms, have children and stop working afterwards, and take care of in-laws. This applies to Southern European countries such as Italy. In France, the “package” is more flexible: women can have children outside marriage and continue to work afterwards without being considered “bad mothers”; there is no notion that children will suffer if they go to a day nursery or are cared for by their father. Diverse family types are more readily accepted, e.g., single parent and reconstituted families and having children out of wedlock. There are also considerable differences between French and Italian family policy, especially the level of social welfare spending reserved for families, and childcare provision. Collective childcare is much more widely developed in France than in Italy and in general, state intervention in the private sphere is much better accepted there, particularly when it concerns raising children. Though the number of day care places for children under three is rising in Italy, preschool children are still taken charge of there primarily by way of intergenerational family solidarity. Informal help from grandparents is crucial: in 2012 in Italy, 53% of preschool children with working mothers were cared for by their grandparents whereas in France the figure was close to 10%. Difficulty in reconciling family and work life in Italy results in both fewer working mothers and fewer births than in France. Social and geographical differences within Italy remain considerable, despite the fact that fertility levels are now similar across regions: more low-educated women stop working than high-educated women, and in southern parts of the country women more often interrupt their occupational activity as soon as they have their first child.

At the time she was killed, Valeria Solesin was completing her analysis of the interview material. She was only just starting the thesis writing, and so did not have the opportunity to fully develop her conclusions and answers to the many questions discussed in her research. Her initial findings show the complexity of fertility decisions and how constraints deriving from a combination of individual history and family, work, social and policy contexts impact on them. In tribute to her, we at INED have assembled her main conclusions in a text we will be submitting for publication to the Revue des politiques sociales et familiales de la CNAF, France’s family welfare office, which also funded Solesin’s thesis work, and to an Italian demography journal.

Source: Valeria Solesin, Allez les filles, au travail, Population and Societies n° 528, December 2015

Contact: Lidia Panico, Arnaud Régnier-Loilier, Laurent Toulemon

Online: November 2016