The precarious housing situation of young people no longer under the jurisdiction of France’s child protection agency, the ASE (Aide Sociale à l’Enfance)

The ASE is in charge of 138,000 children or adolescents in France—1.6% of minors—as children at risk of abuse. The young people enter the system at a wide range of ages, but all of them have to leave it at age 18, when their legal right to agency assistance expires, or, for those awarded a higher education or technical training “contract,” at age 21 at the latest. As soon as young people leave the system they are on their own; among other things, they can no longer rely on the ASE for housing. Drawing on data from the ELAP survey (Longitudinal Study of Access to Autonomy after Placement), INED researcher Pascale Dietrich-Ragon has investigated what types of housing situations young people no longer under ASE protection are in and their experience of them. A considerable proportion had experienced what is called “chronic eviction” both in childhood and during their time under ASE protection. The majority did not choose when to leave that system. And in the period following their departure they experienced multiple difficulties acquiring stable housing.

Young people who had to cope with precarious housing situations early in life

Most young people in ASE care come from socioeconomically precarious backgrounds. In many cases they had already experienced housing difficulties—a common problem for low-income households—while living with their families. Later, placement in ASE care exposed them to being moved back and forth between Agency facilities or foster homes. Nearly half of young people in the system aged 17-20 at the time of the first survey wave had moved in and out of at least three different ASE placement situations: 22% had lived in three, 9% in four, and 17% in five or more. Over one-third reported having had to leave a facility or foster home they would have preferred to remain in—a situation experienced as forced displacement. Though more stable trajectories were observed (half of young people had lived in only one or two placement situations), a considerable proportion of respondents had clearly undergone chronic eviction; that is, repeated forced moves. Above all, in the transition to leaving the system, they all have to cope with that same problem: all of them know they are going to have to leave their placement situation.

Young people experience the scheduled end of ASE coverage as eviction

In a context of budget restrictions and shortage of shelter structures, ASE social workers are called upon to reduce the time young people receive assistance and to move them out of the system to make room for new arrivals. Questioned soon after leaving the system, only 29% of respondents reported leaving ASE care of their own volition or after reaching an agreement with Agency social workers. Conversely, 27% state that the ASE decided when they had to leave, and 38% left because their legal access to Agency protection had expired. The majority, then, did not choose their time of departure (36% say they were required to leave the system too early) and have had to make do with the constraints imposed by the institution. Being evicted from their placement situation therefore impacts all areas of these young people’s lives. The risk of being unhoused is particularly high among this group. 16% of respondents notified by ASE that their time under ASE protection had expired lived in the street after leaving the system, whereas the percentage is close to zero for young people who felt less forced to do so.

Young people in a weak position on the rental market

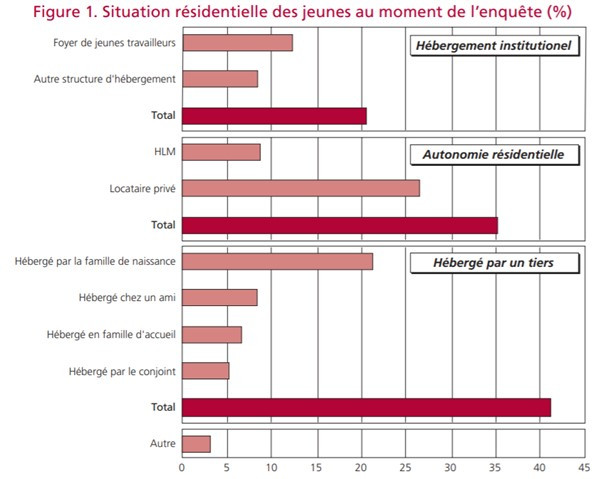

Three housing situations are observed among young people who have left the ASE system: around 20% go back to some type of institutional housing; nearly 40% manage to live under someone else’s roof; while slightly over a third access independent housing (see Figure). In the period immediately following their departure, respondents find themselves at many types of disadvantage on the housing market: they are young and have little resources (28% are unemployed and on unemployment rolls, 6% are unoccupied, while those who do work are in unstable, low-skilled jobs). Moreover, they cannot count on family financial aid or anyone to sign a lease guarantee. Their chances of finding housing on the private-sector rental market are slim, expect for those with a permanent-contract job living in places where rents are not too high.

Source: ELAP V2, 2015, INED-Printemps.

Population: Young people no longer under the protection of or housed by the ASE (and living during the first wave of the survey in ASE placement situations in the 7 departments studied).

Note: Percentages are weighted.

|

The ELAP survey The Longitudinal Survey on Young People’s Autonomy after Placement, or ELAP, is run jointly by INED and the Printemps research laboratory at the University of Paris-Saclay. It is one of INED’s major longitudinal studies. The survey comprises two waves, the first ran from late 2013 to early 2014 and involving a sample of 1622 young people aged 17-20 living in 7 departments with high ASE placement numbers: Nord, Pas-de-Calais, Paris, Seine-et-Marne, Essonne, Seine-Saint-Denis, Hauts-de-Seine, and the second wave done in 2015 with a subsample of the first. ELAP is the first study in France to provide quantitative data on the situations of ASE-placed young people when they leave that system, and thereby to improve knowledge of their living conditions on the eve of their departure from the ASE system and a few months later. |

Source :

Pascale Dietrich-Ragon, « Quitter l’Aide sociale à l’enfance. De l’hébergement institutionnel aux premiers pas sur le marché immobilier », Revue Population n°4-2020

Online: May 2021