Demopædia: a multilingual online demography dictionary

With this multilingual demography dictionary, users can look up the form and meaning of a demography term in their own and other languages.

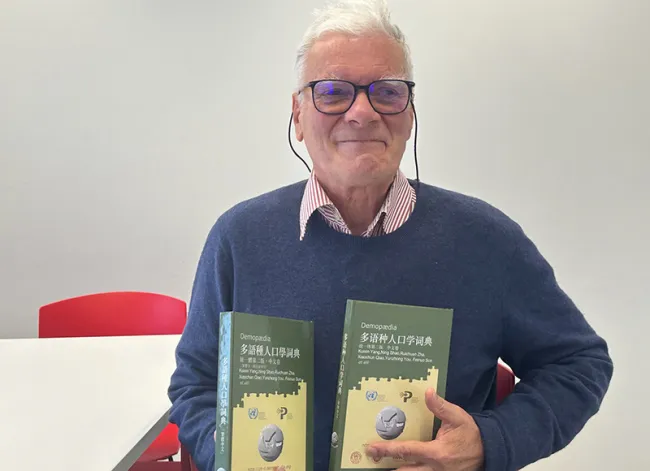

Researcher Nicolas Brouard, who heads the Demopædia project, took part in producing a unified version of the resource and getting it online.

What’s the Demopædia project?

Demopædia is an online platform providing access to the entire set of published editions of the Multilingual Demography Dictionary, editions published over several decades. In a world where research is increasingly international and research studies are constantly overstepping language and institutional borders, this set of dictionaries plays an essential role, ensuring conceptual precision consistent in internationally recognized definitions, facilitating multilingual collaboration, and serving as a highly useful learning tool for students and non-specialists. Demopædia was conceived as a scientific wiki: it, too, evolves over time and can gradually integrate new terms, while maintaining a stable, coherent structure.

How did Demopædia come into being?

The glossary originated in the mid-1950s as a program undertaken by the United Nations International Terminology Committee. The aim at the time was to produce coherent, freely drafted definitions of fundamental demographic concepts. The first editions, published in 1958, reflect just this intention: the texts were independently written and in sync with national scientific traditions. The most complete of these dictionaries is surely the German edition of 1987. They began rewriting in 1960, and the edition they produced included epidemiological concepts and terms. In 2013, it was this German edition that was used to construct what is known as the “unified” edition, which integrates terms that didn’t figure in a considerable number of second editions. Nonetheless, several western-language versions have only been partially unified, a situation explained by the fact that in western Europe higher education training in demography had shifted in large part to English. In this context, countries such as Sweden and Finland deemed there was no need for them to produce a second 1980s national edition.

The situation is considerably different in Asia, where demography training and research continue to draw heavily on widely used and diffused national languages. One such language is Malayalam, spoken in the Indian state of Kerala by more people than speak French in France. This language and academic diversity requires producing fully operational demography dictionaries

Why are there two volumes for the Chinese dictionary?

This was not initially planned; it only became clear that two versions were necessary during preparation of the print editions. The two texts are strictly identical, except for character variants. In fact, the problem appeared when it came time to draw up the index. The traditional classification, by number of lines (which is hardly used today, superseded for the most part by digital coding), so other categorization modes had to be adopted, but they were closely linked to the language systems involved. The Pinyin is mainly used in continental China, while the Zhuyin is used by other Chinese-speaking communities. This decision reflects over 120 years of change in Chinese writing and phonology. It became clear that two distinct volumes were needed in order to preserve index readability and efficiency, but the dictionary form and intention also had to be maintained: a small, printed book with a complete, user friendly index.