The Great War (World War I)

A new collective work: Bouleversements démographiques de la Grande Guerre

World War I took a grim, massive toll in the ranks of both soldiers and civilians. In France, the premature deaths of hundreds of thousands of young men induced a demographic cataclysm: imbalance between the sexes; population ageing, specifically the ageing of the labour force, on whom the work of reconstruction depended; and a birth deficit during the war years.

To mark the centenary of the outset of World War I, INED has published Bouleversements démographiques de la Grande Guerre, a collection of texts that analyse the consequences of the conflict on the French population at different periods and in connection with a variety of phenomena.

A massive slaughter

The extent of the human losses, both civilian and military, caused by World War I (1914-1918) have often led to speaking of this war as a slaughter, a massive sacrifice of life. The data and analysis of those data justify using such terms.

An average estimate is that the Great War caused nearly 10 million deaths, including

- over 2 million Germans,

- nearly 2 million Russians,

- nearly 1.5 million French,

- 800,000 Britons,

- 650,000 Italians.

Among the allies and with the exception of Serbia, France was the country to suffer the greatest number of deaths in relation to its total population.

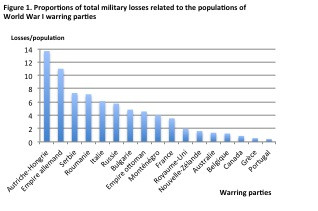

When injured, missing, and captured soldiers are added to military deaths (total military losses), we see that the central empires took the greatest losses, while among the allies, Serbia paid the highest toll (Figure 1).

The most highly populated countries were generally not the ones to suffer the heaviest losses. However, losses seem perfectly proportional to number of soldiers engaged, and there is a similar if somewhat less marked correlation to the size of the given population’s labour force.

Demographic mortality and vitality

Conceived by Martine Rousso-Rossmann and edited by Jean-Marc Rohrbasser, Bouleversements démographiques de la Grande Guerre allows for measuring the magnitude of this slaughter and its effects on the French population.

In Part I, entitled “Les sacrifices de la guerre” [what the war sacrificed] François Héran presents a demographic assessment of the Great War (“bilan démographique de la Grande Guerre”) using the most recent and reliable sources. Jacques Vallin then analyses mortality by generation in France. In the following chapter, France Meslé highlights and examines the particular problem of calculating infant mortality indices in a time of war.

Part II, “La vie malgré tout” [life despite all], studies how the population experienced this trauma. Louis Henry examines what became of young women who had lost their betrothed to the war and widows of remarrying age. Patrick Festy focuses on the war’s impact on French fertility. Peggy Bette studies the particular case of widows and widowhood in Lyon from 1914 to 1924.

Demography in time of war

The first chapter of the book is separate from the rest. It was written by Charles Gide, an economist, in 1916, a moment that he did not know was the central period of the conflict. In a text that is of not only historical but methodological value, he examines how the French population was being redistributed. How are the dead to be counted? And how best to envision population reconstruction?

By taking into account the entire range of demographic consequences brought about by the Great War, this work offers a rare synthesis—the realities and problems discussed in it are seldom handled together—and perhaps the necessary distance for analysing an exceptional historical situation through the prism of demography.

Source: Jean-Marc Rohrbasser (dir.), 2014, Bouleversements démographiques de la Grande Guerre, Ined, Hors Collection

Contact: Jean-Marc Rohrbasser

Online: October 2014